The Iceland National Committee aims to promote sustainable energy development in Iceland, as a part of the World Energy Council’s energy vision. As a member of the World Energy Council network, the organisation is committed to representing the Icelandic perspective within national, regional and global energy debates. The committee includes a variety of members to ensure that the diverse energy interests of Iceland are appropriately represented. Members of the committee are invited to attend high-level events, participate in energy-focused study groups, contribute to technical research and be a part of the global energy dialogue.

Gestur Pétursson is the CEO / Director General of the Icelandic Environment and Energy Agency, which was formed on January 1st 2025, as a result of an institutional reform where the Energy Authority was merged with the Environment Agency. Gestur is a business executive and engineering professional with over 20 years board-level experience, and as a CEO spanning the metal production, energy, utilities, mining, climate tech, health and government sectors. Thereof, he was responsible for all operations of Veitur utilities in servicing over 70% of the population of Iceland with electricity distribution, district heating, potable water and effluent water services. He has specialised in assuming leadership roles focusing on transforming business & organisational culture, improving organisational performance and improving stakeholder relations. Gestur has in the past been a member of various boards as a chair and as a member in Iceland, Canada and Norway. Currently, he is an active member of the Iceland Touring Association board. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Fire Protection & Safety Engineering Technology and a Master's degree in Industrial Engineering from Oklahoma State University.

Baldur Pétursson is a Manager - International Projects Manager, Unit of International Cooperation, Icelandic Environment and Energy Agency.

In possession of extensive domestic and international experience in administrative work for many years, he has worked as International Projects and Public Relations Manager at the National Energy Authority in Iceland, working on various international projects and programs, e.g. working in cooperation with the Financial Mechanism Office in Brussels, (FMO, EEA Grant), World Energy Council, etc. He was also the Head of Unit within the Ministry of Industry and Commerce for several years, as well as a Member and/or chairman of several domestic committees and reports on industrial sectors. Moreover, he was Counsellor at the Icelandic Mission to the EU in Brussels, Member of the Board and later Executive Alternate Director at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London, Member of the Board at Islandsbanki in Iceland (2010-12). He has also served as a member of several international committees e.g. within, Nordic Energy Research, EEA, EBRD, EU, EFTA, OECD, IPHE, NORA, Nordic Ministerial Council, Energy Charter, World Energy Council (WEC), WEC Europe Committee and WEC Strategy and Communication Committee.

His educational background includes an MSAS in International Business from Boston University in the United States, Business Administration from the University of Iceland and in possession of the Certification Assessment of the Eligibility as Chief Executive Officers and Members of the Boards of Directors of larger Financial Undertakings approved by the Financial Supervisory Authority in Iceland, 2010.

Energy in Iceland

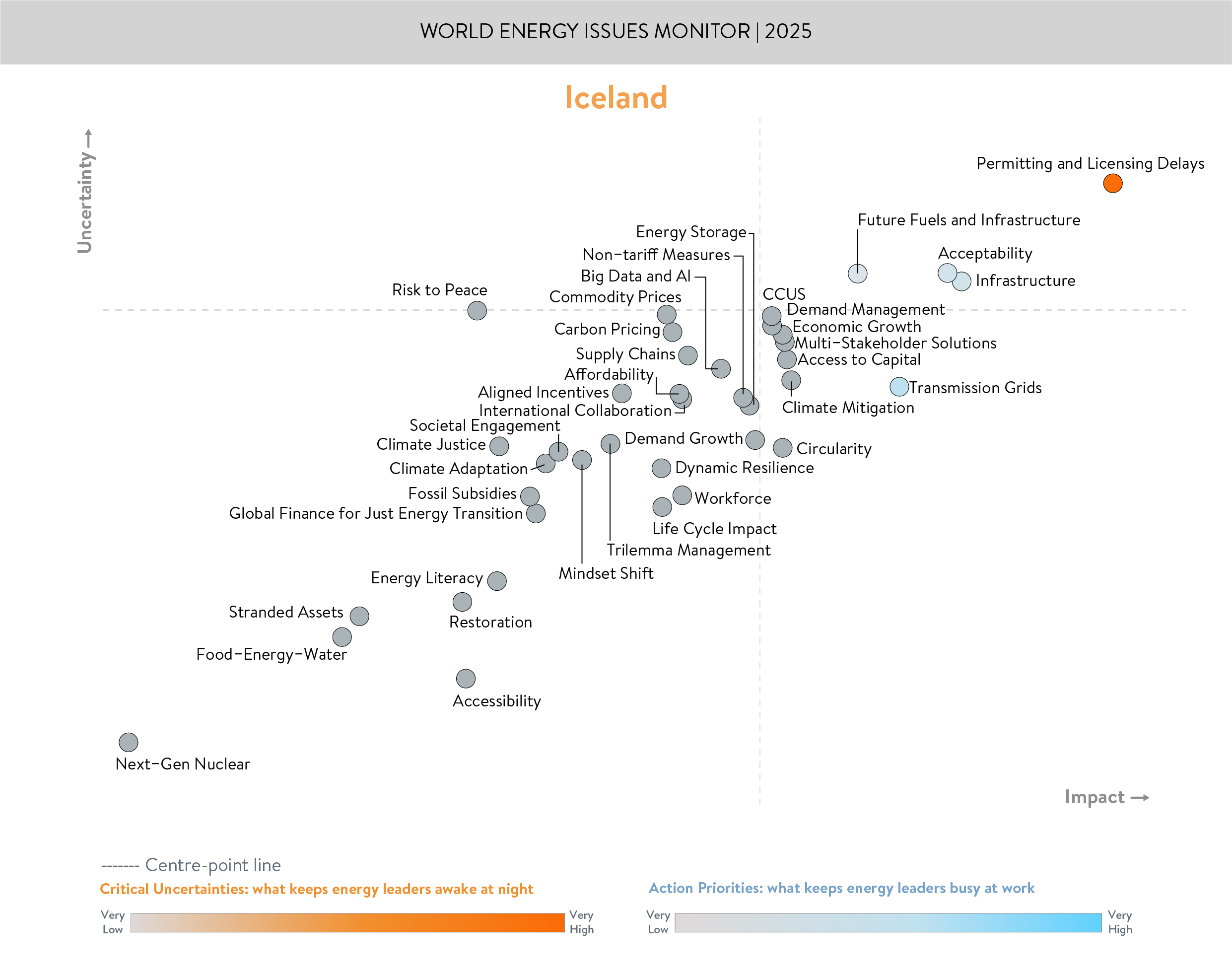

The 2025 World Energy Issues Monitor presents a global snapshot of the evolving energy landscape, offering insights into national priorities, emerging risks, and energy transition readiness. For Iceland, the survey results confirm both its international leadership in renewable energy and the growing complexity of sustaining that leadership amid rising climate ambition, economic transformation, and technological disruption.

Iceland is one of the few countries in the world where renewable energy powers the entire electricity and 99% of the heating systems, owing to its exceptional geothermal and hydropower resources. However, this achievement masks underlying challenges that must be addressed to complete the full transition to a carbon-neutral society. The fishing fleet, heavy-duty transport, aviation, and some industrial processes still depend on fossil fuels. Moreover, the energy system’s governance, infrastructure, and financing models must adapt to an increasingly dynamic, integrated, and decentralized energy reality.

The World Energy Issues Monitor identifies critical uncertainties issues that are both highly impactful and unpredictable and action priorities, where clear, coordinated intervention can accelerate change. For Iceland, the current energy transition is at a crossroads. While much has been achieved, the most difficult phase lies ahead: addressing institutional bottlenecks, social acceptance, emerging technologies, and sectoral integration.

CRITICAL UNCERTAINTIES FOR ICELAND

Permitting and Licensing Delays. As energy projects become more diverse and complex, permitting and licensing procedures are too time-consuming, difficult and slowing down normal processes. This development is important to analyze, simplify and reverse. The current framework, designed for traditional energy development, is proving too slow and fragmented for modern needs. Multiple agencies, overlapping mandates, and lengthy appeal processes can stall clean energy projects for years. This is not only a procedural problem, but an economic one, as delays translate into missed investment opportunities, supply constraints, reputational risk and higher levelized costs of energy. A modern permitting regime should include digital platforms, clearer environmental impact assessment rules, and integrated community engagement processes. Iceland has an opportunity to lead by example with a permitting model that is both efficient and complete. The new government has announced that the whole permitting process will be reconstructed towards faster track, simplicity and quality process.

Acceptability. The tension between energy infrastructure expansion and environmental or local concerns has had a major impact on Iceland’s policy landscape. Projects that promise national climate benefits may still be opposed at the local level if perceived to harm landscapes, tourism, or ecosystems. Wind energy development has faced vocal resistance. Strengthening project legitimacy requires embedding acceptability into the design phase. Social impact assessments, co-ownership opportunities for communities, benefit-sharing mechanisms, and transparent communication are essential. Iceland can draw lessons from international best practices in public participation and landscape stewardship to ensure that social trust is a foundation, not a barrier, for the energy transition.

Future Fuels and Infrastructure. Iceland’s path to decarbonization increasingly depends on the successful deployment of alternative fuels such as hydrogen, ammonia, synthetic fuels and biofuels. These are particularly relevant for maritime transport, aviation, and industrial heat. Yet, future fuels come with high uncertainties: infrastructure requirements are significant, safety standards are evolving, and demand is not yet mature. Iceland will need to identify niches where these fuels can be piloted effectively, such as at harbors, shipping routes, or industrial complexes. Strategic infrastructure mapping, pilot zone designation, and partnerships with neighboring Nordic, European and North American countries can help Iceland build the ecosystem needed for these new energy carriers.

Infrastructure. Beyond electricity generation, Iceland’s energy infrastructure must now serve a wider, more complex system. This includes electric mobility, charging networks, decentralized solar installations, smart grids, and green fuel supply chains. Legacy infrastructure is not designed for such flexibility. Moreover, as the economy digitalizes and electrifies, ensuring resilience against cyber threats, supply chain disruptions, and climate-related shocks becomes vital. Infrastructure development must therefore be not just expanded but also reimagined to meet 21st-century challenges. This includes investing in predictive maintenance systems, real-time monitoring, and integrated planning tools that align energy, transport, housing, and land-use policies.

Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS). Iceland’s unique geological conditions have enabled globally pioneering work in CCUS, most notably through Carbfix, which mineralizes CO₂ in basaltic rock. While promising, the scalability of CCUS for national and export-oriented purposes is still uncertain. Regulatory clarity, long-term financing models, liability frameworks, and cross-border cooperation will all determine its role in Iceland’s decarbonization pathway. There is also a need to align CCUS with the country’s broader industrial strategy—can captured CO₂ be used in building materials, agriculture, or synthetic fuels? If Iceland integrates CCUS as a cornerstone of its clean tech brand, it must also ensure that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) safeguards are upheld.

ACTION PRIORITIES FOR ICELAND

Transmission Grids. The transmission grid is the backbone of Iceland’s clean energy system. As energy use becomes more distributed and variable, grid flexibility, redundancy, and intelligence will define future reliability. Electrification of transport, new industrial loads, and expanded rural generation require a modernized, adaptive grid. Planning must consider not only technical capacity, but also socio-environmental impacts and potential interconnection with other markets. Strategic grid investments can also serve regional development goals by enabling remote communities to access clean energy jobs and services.

Climate Mitigation. With its electricity and heat supply almost fully decarbonized, Iceland’s climate mitigation challenge now centers on the demand side: transport, agriculture, fisheries, and land use. These sectors are harder to transform but essential for achieving net-zero. Stronger emissions reporting, sector-specific roadmaps, and targeted incentives will be needed. Iceland should also strengthen its use of nature-based solutions, including reforestation, wetland restoration, and soil carbon enhancement, to complement technological measures. Integrating climate mitigation into national development planning—across ministries and regions—is key to aligning economic policy with environmental responsibility.

Access to Capital. The clean energy transition in Iceland will require both scale and speed in financing. Iceland’s electricity system was built without subsidies on commercial terms, making renewable electricity generation a backbone of the country’s economy. However, traditional project finance may not suffice, particularly for emerging sectors with uncertain revenue streams. Iceland must explore blended finance tools that combine public guarantees with private capital, enabling banks and investors to support innovative projects. Financial literacy on climate risks and green lending should be promoted within the domestic banking sector. In parallel, Iceland should deepen engagement with EU and Nordic investment platforms to expand access to concessional loans, grants, and equity financing.

Multi-Stakeholder Solutions. No successful energy transition is top-down. Iceland’s strength lies in its cohesive society, well-educated population, and strong institutions. These assets should be mobilized through deliberate, participatory governance. Energy strategies should be co-created with youth, municipalities, industry groups, and underrepresented communities to ensure legitimacy, innovation, and equity. Citizen assemblies, energy forums, and regional transition compacts could provide platforms for structured dialogue and local empowerment. Academic institutions also have a vital role to play in providing independent analysis, policy evaluation, and skills training.

Economic Growth. Energy transition is a lever for national renewal. Iceland can reposition itself as a green innovation hub, exporting expertise in hydropower, geothermal energy, renewable grid management, CCUS, and circular economy solutions. Clean energy can power value-added industries such as sustainable data processing, sustainable food production, electrified industry and high-quality tourism. Policies that align workforce training, research funding, and trade strategies with green growth objectives will help unlock this potential.

CONCLUSION

The 2025 World Energy Issues Monitor confirms that Iceland is well ahead of most nations in its renewable energy transformation—but it now faces a more complex, strategic phase of transition. The challenges are no longer purely technical; they are institutional, financial, and societal. Addressing permitting and licensing delays, deploying future fuels and infrastructure, managing acceptability, upgrading national infrastructure, and scaling CCUS will define the next decade of Iceland’s energy policy.

Simultaneously, decisive progress is needed on transmission grid modernization, accelerating climate mitigation, unlocking access to capital, enabling multi-stakeholder solutions, and leveraging the transition for economic growth. Iceland’s ability to lead will depend on integrated planning, bold innovation, and inclusive governance.

With coordinated action, strategic vision, and continued commitment to sustainability, Iceland can complete its transition while serving as a global exemplar for resilient, inclusive, and science-based energy transformation.

Acknowledgements

Iceland Member Committee

-

Baldur Pétursson, Jón Á. H. Þorvaldsson, Icelandic Environment and Energy Agency

-

Freyja Björk Dagbjartsdóttir and colleagues, Landsvirkjun, Iceland

-

Samorka, Federation of Energy and Utility Companies, Iceland

Downloads

Iceland Energy Issues Monitor 2025 Country Commentary

Download PDF

World Energy Issues Monitor 2025

Download PDF

Iceland World Energy Trilemma Country Profile 2024

Download PDF