The Belgium National Committee aims to promote sustainable energy development in Belgium, as a part of the World Energy Council's energy vision. As a member of the World Energy Council network, the organisation is committed to representing the Belgian perspective within national, regional and global energy debates. The committee includes a variety of members to ensure that the diverse energy interests of Belgium are appropriately represented. Members of the committee are invited to attend high-level events, participate in energy-focused study groups, contribute to technical research and be a part of the global energy dialogue.

William D’haeseleer is Full Professor in the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Leuven (KU Leuven), Belgium. He teaches courses in the domain of Energy Technology & Management (Thermodynamics, Nuclear Energy, Thermal Systems, Renewable Energy). His research is mainly situated in the areas of Energy Conservation & Energy Management, Energy & Environment, Energy Systems, and Energy Policy. He is Director of the KU Leuven Energy Institute. W. D’haeseleer graduated as Electro-Mechanical Engineer (option Energy; 5y program – “Diplom-Ingenieur”) and MS in Nuclear Science & Engineering from the KU Leuven in 1980 and 1982, respectively. In December 1983, he obtained another MS degree in Electrical Engineering (Plasma Physics) from the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-M), USA. He received his Doctoral Degree (PhD) from the UW-M in May 1988. From 1988 till 1993, he resided in Germany, at the Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik in Garching-bei-München, after which he was active in the Belgian engineering consulting company Tractebel Engineering. As of 1996, he holds a full professorship at the KU Leuven. He has been a Fulbright Fellow and is an elected member of the Royal Academy of the Sciences and the Arts of Belgium (KVAB).

Energy in Belgium

ENERGY ISSUES IN MOTION – UNCERTAINTIES ABOUND

Given the prevailing uncertainty and confusion, one might argue there's little of relevance to say—yet equally, there's much to clarify, especially the context. A brief overview of Belgium’s energy background is therefore useful.

After the closure of its coal mines in the latter half of the 20th century, Belgium no longer has domestic fossil fuel resources. Since the 1970s, nuclear energy has conventionally been treated as a primary energy source, and in recent years, the role of renewables—though still limited—has become increasingly significant. For petroleum, Belgium depends on global crude oil markets but benefits from four domestic refineries in the Port of Antwerp, which produce secondary petroleum products traded internationally. As for natural gas, the absence of domestic reserves is offset by a robust infrastructure: nearly 20 cross-border pipeline entry points, an LNG terminal in Zeebrugge, and a diverse set of international contracts ensure reliable supply. For both oil and gas, prices are dictated by European and global markets.

Belgium’s wholesale electricity sector has been shaped primarily by its domestic generation mix (nuclear, natural gas, and renewables—following closure of its last coal plant in 2016). It also relies heavily on cross-border transmission links, strongly related to the liberalization of the European electricity market.

In the recent past, Belgium has, like many other counties, faced global disruptions: post-COVID recovery, supply chain issues, protectionist shifts, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict—all contributing to rising costs and worrisome inflation concerns.

But as a shadow over its energy policy, Belgium has been ‘victim’ to the self-inflicted festering wound of the highly ideologically controversial nuclear phase-out law, agreed upon mid 1999 at the behest of the ‘green’ coalition parties. For over two decades, this policy has been a source of division and indecision across successive coalition governments. Given that nuclear accounted for around 55% of electricity generation until 2011, many saw a full phase-out by 2025 as unrealistic. Others, however, viewed it as a courageous step to eliminate that nuclear ‘nuisance’.

Motivated by the falling costs of solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage—and buoyed by the EU’s Green Deal and Fit-for-55 targets—the 2020-2024 Belgian government (again including ‘green’ parties) committed to definitively implement the full nuclear phase out by 2025. This no-nuke stance was ‘encouraged’ by the low availability of nuclear plants between 2012 and 2019, albeit by varying causes.

However, critics noted that this full-exit objective overlooked the abrupt timeline: retiring 6000 MWe of nuclear capacity within just three years (2022–2025). The capacity shortfall was to be covered by subsidized natural gas plants under the Capacity Remuneration Mechanism (CRM).

Achieving this ‘no-nuke’ goal demanded a comprehensive strategy led by the energy minister. In addition to CRM-supported gas plants, the plan aimed for significant offshore wind expansion, an energy island in the North Sea, and subsea links to Denmark, Norway, Ireland, and UK. It also included large-scale upgrades to the onshore grid (notably the Ventilus and Boucle-du-Hainaut projects), modernization of distribution infrastructure, and steps toward electrifying transportation, heating, and industry—referred to as "sector coupling."

For some time, the nuclear phase-out plans were welcomed by the no-nuke supporters, while skeptics reluctantly had to accept them. The expected rise in CO₂ emissions from new gas-fired turbines was justified under the EU Emissions Trading System, despite higher carbon prices increasing industry costs. Though the overall cost-benefit analysis seemed to be ‘acceptable’, transparency of the full picture remained an issue.

A key challenge remains the need for substantial short-term investments—in grids, potential hydrogen infrastructure, CRM subsidies, and more—while benefits would only materialize in the long term. This raised concerns over Belgium's industrial competitiveness, as high energy costs could drive businesses abroad, preventing them from ever benefiting from future price reductions.

Concrete implementation hurdles emerged early, however: legal and public resistance to new grid infrastructure (Ventilus & Boucle du Hainaut), permitting issues for gas plants linked to NOx emissions, and growing worries about methane leakage from the natural gas supply chain. Despite these setbacks, confidence in achieving a full nuclear exit remained—at least for a time.

But then, by late 2021 and early 2022, the European energy landscape changed dramatically due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, triggering a natural gas crisis and soaring prices for both gas and electricity. This crisis cast serious doubt on the strategy of using natural gas as a transitional fuel.

Faced with growing concerns over energy dependence and affordability, the then Belgian government came to realize that the planned full nuclear phase-out by 2025 became untenable. Following difficult intra-governmental discussions, a decision was made in March 2022 to extend the operation of two 1GW nuclear reactors until 2035.

Meanwhile, however, the energy ‘circumstances’ had continued to evolve. Engie/Electrabel, Belgium’s nuclear operator, had long advocated extending nuclear plant operational lifetimes but stressed that this required a formal government decision before the end of 2020. The government's continued delay frustrated the company, which by early 2021 announced it was no longer pursuing nuclear extensions, instead shifting focus to renewables and natural gas. (Noteworthy, Engie was formerly GdF/Suez—Gaz de France/Suez.)

Following prolonged and complex negotiations, Engie/Electrabel and the Belgian government finally reached a deal in mid-2023 to set up a joint undertaking to extend the operation of the Doel 4 and Tihange 3 reactors. A key requirement was the imposition of a cap on Engie’s liability for historic nuclear waste.

The June 2024 elections produced a new government without ‘green’ parties. During coalition talks, the incoming government—officially in office from February 1, 2025—adopted a more favorable stance toward nuclear energy. Meanwhile, several setbacks emerged for the previous ‘green’ energy minister’s initiatives, including Denmark’s cancellation of the planned interconnector, public opposition to rising grid tariffs, and criticism over the costly energy island.

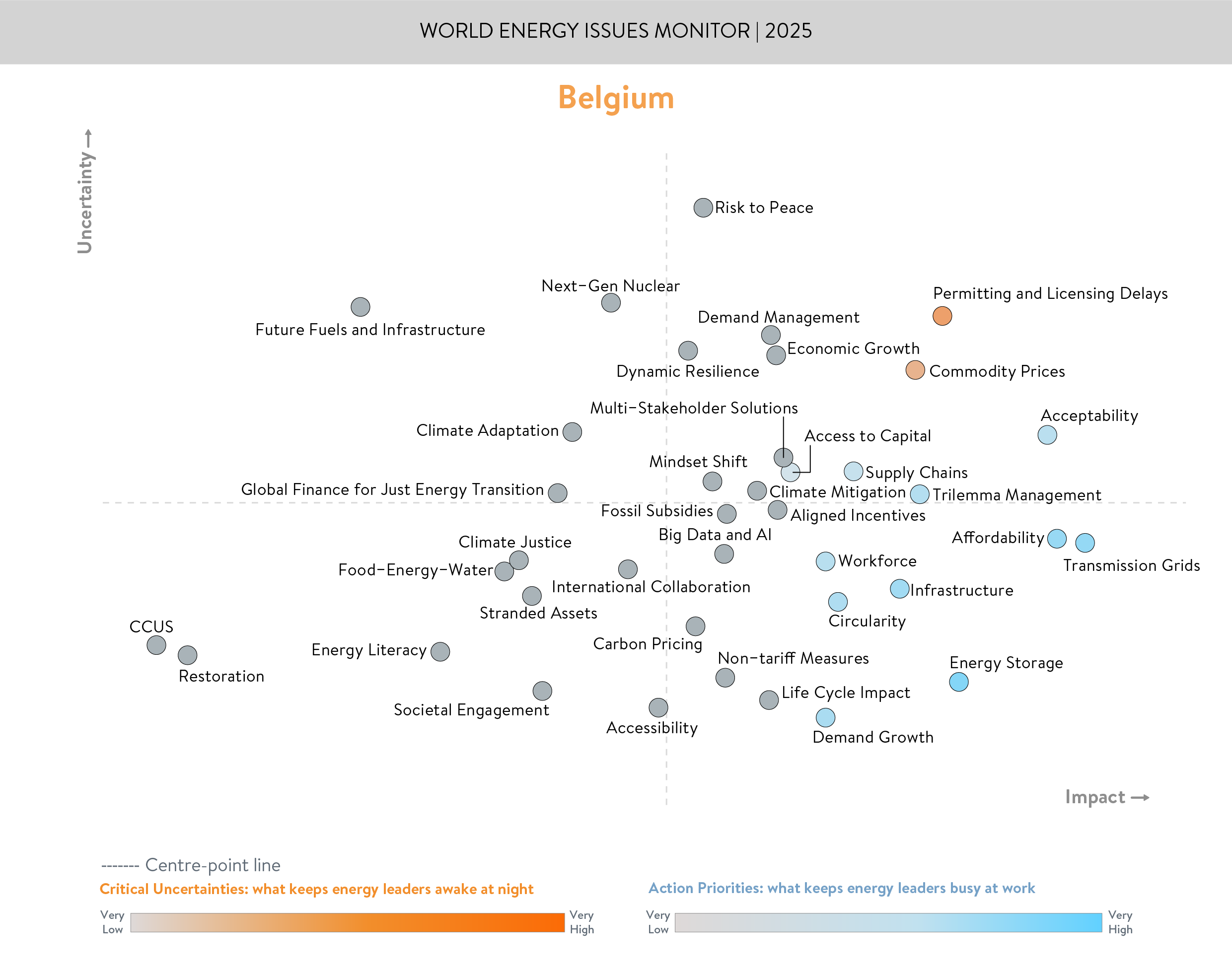

Given that uncertainty context, the outcomes of the Issues survey in January 2025 (averaged over 60 expert respondents) are unsurprising. Except notably, CCUS is considered as of little important in Belgium, while Next-Gen nuclear is viewed as only moderately impactful but highly uncertain.

Acknowledgements:

Belgium Member Committee

William D’haeseleer

Downloads

Belgium Energy Issues Monitor 2025 Country Commentary

Download PDF

World Energy Issues Monitor 2025

Download PDF

World Energy Issues Monitor 2024

Download PDF